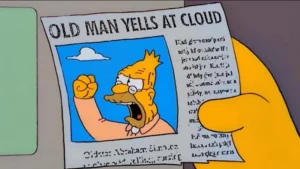

DISCLAIMER: This article is not simply going to be another example of an old man yelling at a cloud.

It’s also not going to be a discussion around me staring into the middle distance and yearning for the “good ol’ days“.

But I will put it bluntly

There is an epidemic of shouting masquerading as singing, at least to my mind and my ear. And today I want to talk about why.

Over the years

To begin with, I’ve lost count of the number of events where every singer was just yelling their guts out. I’ve even seen singers step away from the microphone to show how loudly they can bellow their lyrics—it’s part of their performance piece. I’ve seen performers get gigs for not much more reason than they can belt notes louder than their peers. I’ve even been singing as part of a group, where when someone starts yelling their part, people think that equates to a more emotional performance.

What exactly is causing this? And what are the highest quality singers actually doing that sets them apart from some that might be accused of yelling?

Before we judge such singers too harshly…

… are there reasons behind why many resort to yelling? Are there tripwires that cause some singers to miss out on the path to higher quality?

I’m not for a second looking to justify or exonerate bad singing, but I also want to be clear that the voice has its complications. It would therefore be remiss to not discuss some of the physiological factors at play in this trend.

What do I mean by ‘yelling‘?

When you hear someone shouting across a room to get someone’s attention, or yelling at a football match, or bellowing an order to a subordinate, this is yelling. We all intuitively know the sound, both having heard others yell, and having felt it in our own bodies when we’ve done the same.

NOTE: As a very quick prima facie argument against yelling of any kind as a valid foundation for singing, ask yourself: how long do you feel you can keep up any of the above activities before your voice would give out or hurt? How long could you continuously yell as if at a football match before your voice goes hoarse or you feel pain?

Now ask yourself: if you were trying to vocally perform for hours every night, how sustainable would this approach be? Maybe for the odd 10–20 minute set once a month you could get away with it, but it’s far from an optimal or commendable approach.

I trust you now grasp just how unsustainable it is to approach singing like it was all about forcing one’s way to the top notes.

How does this happen?

When someone yells, what is going on mechanically is best described as a megaphone-type structure. The vocal folds at the laryngeal level generate sound, and the vocal tract is wide-open and relatively disengaged. This creates an effect like someone speaking into the narrow end of the cone of a megaphone.

Think back to the last time you heard someone whose singing could be described as shouty. You may have noticed that such singers are not yelling every note. Instead, this shouty quality tends to creep into people’s voices the higher they wish to sing.

This shouty quality typically progresses fairly rapidly as soon as the singer encounters difficulty with singing higher. The phenomenon is highly vowel dependent. Sometimes it is a binary switch, but generally this quality creeps in gradually.

Why does this happen? Why do singers opt for this approach?

As we sing higher, we need higher and higher subglottal air pressure to sustain the note. This increases the air pressure in the vocal tract.

This higher air pressure also acts upon the vocal tract. For less skilled singers, it is hard to know what to do with this sensation. They feel pressure inside their throat and typically experience a physiological response to want to release it.

There is also the tendency of singers to apply excessive force to reach higher notes, even beyond the necessary increase. To sing higher notes well requires fine motor control of the larynx and vocal folds, independently of air pressure. But singers who do not yet have this control tend to apply extraordinarily excessive air pressure to literally force the larynx to tilt.

To the inexperienced singer, they have two options to alleviate this sensation of pressure:

1) Open the vocal tract (megaphone/yelling) — dumps the extra pressure. This initially produces a loud sound but is unsustainable and inefficient.

2) Drop the volume — reduces air pressure across the system. This typically shifts the sound into a lighter head voice/falsetto quality.

In both cases, the singer diverges from their previous approach and from the vocal quality they had been delivering.

In option 1, the vocals become shouty and bellowed (think Idina Menzel – Frozen). In option 2, the vocals suddenly become light (think Sam Smith – Lay Me Down).

So what is the solution?

As it happens, there is a third option, but it isn’t necessarily obvious.

3) Keep the vowel the same, and keep the volume the same.

Start with the correct vowel and a consistent volume, and learn to stay the course. To the inexperienced singer, this can seem like an impossible knife-edge of control.

This means NO yelling. No going light. No bailing out to options 1 or 2. We aim to keep everything controlled as we move higher—controlled, but without tightness or force. This is the third option.

It’s what you hear when you hear most great classical singers, and the best pop singers (Stevie Wonder, Peabo Bryson, etc).

Sidenote: When I say vowel and volume remain “the same”, I’m being imprecise. Subtle vowel modification is required, but the key point is maintaining congruence so the listener perceives no tonal shift.

Conclusion: There are genuine reasons people yell

The physiological difficulties of singing tend to push people toward option 1 or 2 as the easy way out. It’s like lifting a heavy object with poor form: the body chooses a damaging shortcut.

This third option requires significant co-ordination and practice. The higher we sing, the more air-pressure and vocal fold control must be mastered. The higher and more controlled we wish to be, the more precise the instrument must become.

This is fundamentally a high-level skillset. Few people invest the time; most take the short road, even if it’s a short one.

If after reading this, you feel like you are falling prey to this and would like help resolving these issues in your voice, you can book in to work with me below.